How do we know if a book is good?

Perhaps, books are recommended to you by friends, family, or colleagues, or you seek out literary reviews or blogs to find your next good read. Another way books are recommended to us or are conferred a “quality stamp” is by literary prizes, the most prestigious of which is perhaps the Nobel Prize in Literature. For a laureate, winning the Nobel Prize certainly has an effect on book sales and helps to bring their work into the public eye. But does the Nobel Prize in fact reflect “Nobel quality” or anything beyond the capricious tastes of a Swedish literary committee?

The merits of the chosen Nobel laureate are often the cause for near-yearly controversy and much discussion – but the candidates left out is a matter just as debated. Among the names that have been famously ignored for the prize are Jorge Luis Borges, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Salman Rushdie, and Leo Tolstoy. Indeed, the Nobel Prize has been variously criticized: for being arbitrary, for awarding lightweight or obscure writers, and for political and Eurocentric biases of the appointing committee. Does that mean that there is no amount of quality distinguishing books of Nobel laureates from those of their peers?

The shape and beauty of stories

The question of what literary quality is, and how and by whom it is measured is a continuing enigma central to the Fabula-NET project. The real question is, do we appreciate a book for its “quality stamp” (whether the stamping is done by friends, bloggers, or institutions), or do award-committees such as the Nobel Committee stamp a book for its qualities?

Recently there has been some claim that certain narrative arcs are more likely to captivate readers, and that stories have a limited amount of basic shapes or plots that have bearing on literary appreciation. Scholars like Matthew Jockers have studied sentiment-arcs as a proxy for plot, that is, the way the emotional evocation of narratives goes up and down in a certain shape. Plot and emotional vocabulary go hand in hand: a particularly thrilling passage is bound to be described with a certain nerve-wringing vocabulary, and a sad passage with a negative tone of voice. Simply put: a sentiment-arc of a tragedy would go down in the end, while that of a comedy would go up.

In our first post we described our method of using fractal analysis to examine not only the simple shapes of such sentiment-arcs, but their dynamics: the evolution and shifts between positive and negative feelings in the narrative. What this tells us is not just how the sentiment-arcs of stories look, but how the highs and lows of emotional vocabulary are distributed and whether these dynamics exhibit a specific pattern which repeats fractally on different times-scales. How, in other words, the story-arc is experienced and whether there is a certain symmetry or fractal beauty to it.

When looking at fairytales, it seems that certain fractal patterns are indeed predicative of the stories’ appreciation by readers, as stories with certain dynamics tend to be rated higher on Goodreads. True, fairytales are short stories that may follow similar patterns – which is why we should ask if the same might be true for longer, more complex texts. Can fractal analysis help us distinguish the most loved novels – or the ones of more prestigious distinction? So, we ventured out to learn if there is something in the dynamics and pace of their sentiment-arcs that especially distinguishes the writing of a Nobel laureates. Investigating the literary quality of Nobel laureates is an especially daunting task because, firstly, the choice of Nobel laureate may be subject to more than just an estimation of quality (read biases), and secondly, because the Nobel Prize is given to one among many valid choices, so it might be difficult to distinguish the writing of Nobel laureates from that of their competitors (the first Nobel laureate of literature in 1901, Sully Prudhomme was considered for the prize along with Leo Tolstoy and Émile Zola, for example).

To test this, we examined authors in the Chicago corpus, which spans 9089 novels by mainly US authors published between 1880 and 2000. The corpus contains key works of US Nobel laureates: Ernest Hemingway, Toni Morrison, and John Steinbeck, among others, but also of non-US laureates, such as Samuel Beckett and Knut Hamsun. Moreover, many authors in the corpus have won other prestigious awards like the National Book Award, such as Don DeLillo, Joyce Carol Oates, and Philip Roth. To ensure that our investigation was similar to the actual selection process of a Nobel laureate, we compared Nobel-winning-authors to their contemporary competition. For each book, we examined, by a Nobel laureate, we included all novels by non-Nobel-winning authors published one year before and after the “Nobel”-book.

Reading droughts and tides

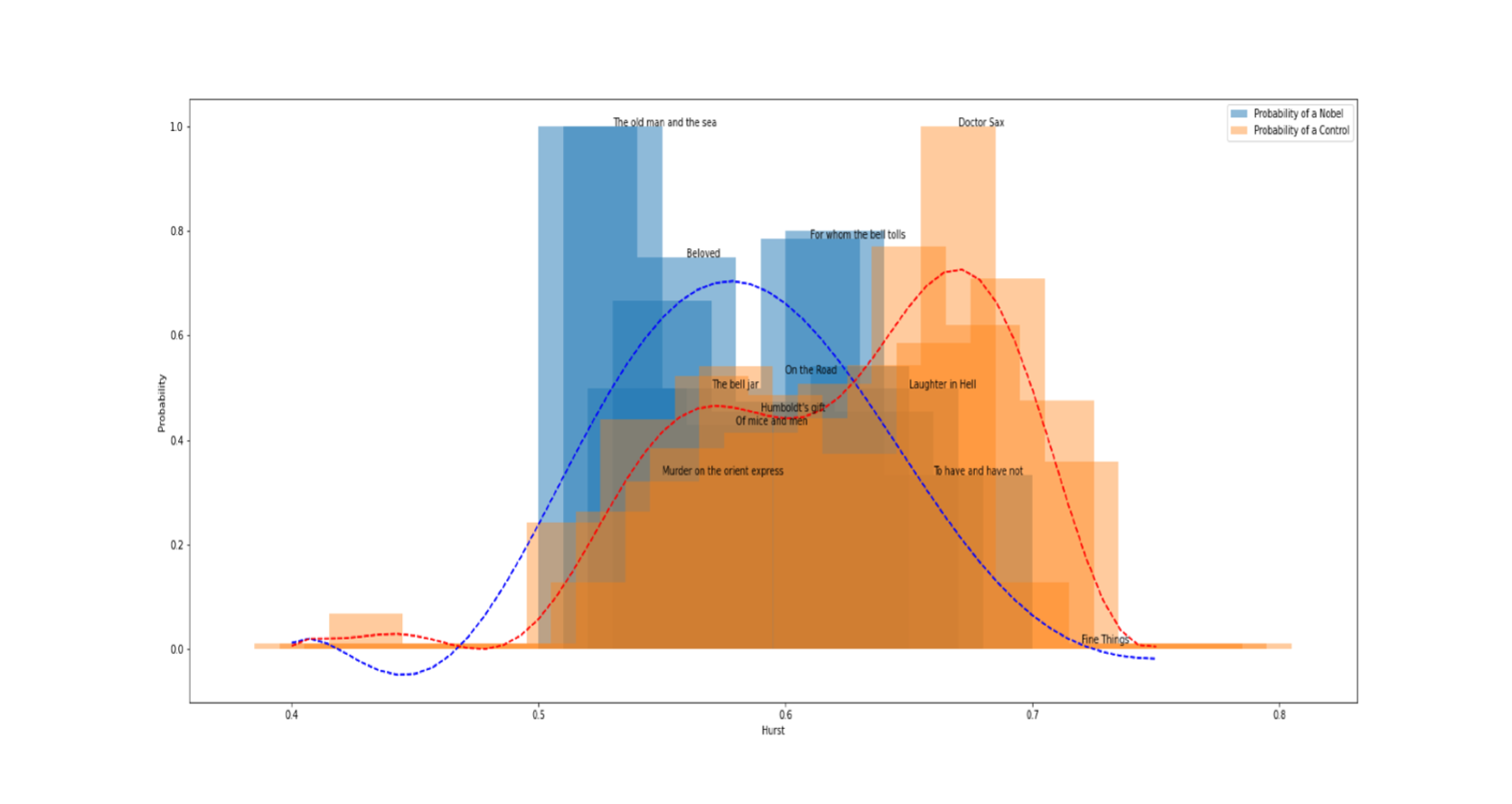

“Reading” the stories through a “sentiment dictionary”, we attributed positive or negative emotional values to each sentence which, when put together, sketches the sentiment-arc of each book. To assess the dynamics of each arc, we calculated its Hurst exponent. The Hurst exponent was first used to measure the pattern of rain- and drought-conditions over long periods of time in the Nile Basin, but it can equally measure the pattern of stories’ ups and downs. A Hurst score below 0.5 indicates that a story sticks to a certain base-sentiment. Such a sentiment-arc oscillates around an average, so that a positive emotion is followed by a negative and then a positive and so on. A value above 0.5 indicates that emotional intensity develops across longer spans of time. As in our study of Andersen’s fairytales, we supposed that there is a Hurst “sweet spot”, a certain interval of H score that is more appreciated by readers. To captivate readers, a sentiment arc develops across a certain span of time, but it is probably neither completely self-similar or predictable, nor completely random or unpredictable. Next, we ran a series of classifiers based on the Hurst scores and sentiment-arcs of the books to see whether these factors can be used to predict whether the book was written by a Nobel-winning or non-Nobel-winning author. As you can see in the figure below, based on Hurst score and sentiment-arcs of books, classifiers are able to tell Nobel laureates from other authors.

In fact, it seems that the works of Nobel laureates tend to fall into a certain “sweet spot”, between H 0.53 and H 0.61, while it is less probable that books outside this interval belong to a Nobel laureate. It should be noted that there is a considerable overlap between the two groups: there are books by non-Nobel-winning authors that have the same qualities as books by Nobel laureates – as there should be. After all, only one Nobel Prize in Literature is awarded each year and it is selected among many valid choices. Moreover, there are books by Nobel laureates, such as Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, that does not fall in the Hurst “sweet spot”, with a score of H 0.68. Still, a general pattern is visible: books by Nobel laureates tend to be overrepresented around a certain scored compared to non-Nobel-winning authors’ books.

It is important to remember that a “good” Hurst exponent does not equal literary quality – it would be foolhardy to think that there is one definite measure for literary quality, where many factors are bound to weigh in. Nevertheless, fractality does seem to predict Nobel laureates from other writers in the corpus, despite there being famous authors in both groups. Certainly, our study suggests that we should take a closer look at fractality when asking about literary quality.

Our article will be presented at NLP4DH and included in the proceedings.

References:

Bizzoni, Y., Peura, T., Thomsen, M. R., & Nielbo, K. L. (2022). Fractal Sentiments and Fairy Tales Fractal Scaling of Narrative Arcs as Predictor of the Perceived Quality of Andersen’s Fairy Tales. NLP4DH, 1–15. https://jdmdh.episciences.org/9640

Jockers, M. (2014). A Novel Method for Detecting Plot. https://www.matthewjockers.net/2014/06/05/a-novel-method-for-detecting-plot/

Peschel, S. (2019). How the Nobel Prize Affects Book Sales. Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/how-the-nobel-prize-affects-book-sales/a-51607765

Reagan, A. J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D., Danforth, C. M., & Dodds, P. S. (2016). The Emotional Arcs of Stories Are Dominated by Six Basic Shapes. EPJ Data Science, 5(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1